Networking is a fundamental concept in cloud computing. It allows us to connect various resources within the cloud environment and also for external communication to the internet or private data center. In this series of articles, I hope I can give you enough basic understanding to get it started in the cloud.

Cautionary note. My experience is mostly on Google Cloud Platform and a little bit on Amazon Web Services. While I try to make it as general as I can, there ought to be some bias reflected on my train of thought and word choice in these articles. I might also give an example that is cloud-provider specific. However, I hope that with a good background understanding of the basic concept and the services offered by the cloud provider of your choice, this could give enough stepping stone.

Prerequisites. I kinda assume basic knowledge of day-to-day computer networking on a personal device (for example, I don’t need to explain again what a wifi is and what RJ45 cable is for, at least on a surface level). I also assume knowledge of binary number and their operations (and with it, obviously I’d assume at least basic arithmetic knowledge). If you don’t know this already, a 15 minutes Googling for each topic is probably enough to teach yourself about them.

With that being said, let’s get started.

Network?

So, what does “network” means? If you search it up on Wikipedia, it will shows you a lot of different, somewhat related in some sense, answer. Of course what we are interested in right now is the one about computer network, which is defined as “a digital telecommunication network”, where telecommunication network is said to be “allowing communications between separate node”. There is our keyword: communicating nodes. Nodes here can be thought (loosely) as a computer or an abstraction of one. Historically this was used to interconnect several computers in an organization to do something (that is, those computers can exchange information with each other). Nowadays, we already use one of the most well-known example of networks: the internet. Another example would be a Local Area Network (LAN). It’s a private network which (typically) operates in a single physical location. For example this would be when you wire several computers on your house to a router. The router would then route the communication to its intended recipient. This would then allows you, for example, to exchange files or to play games together over LAN.

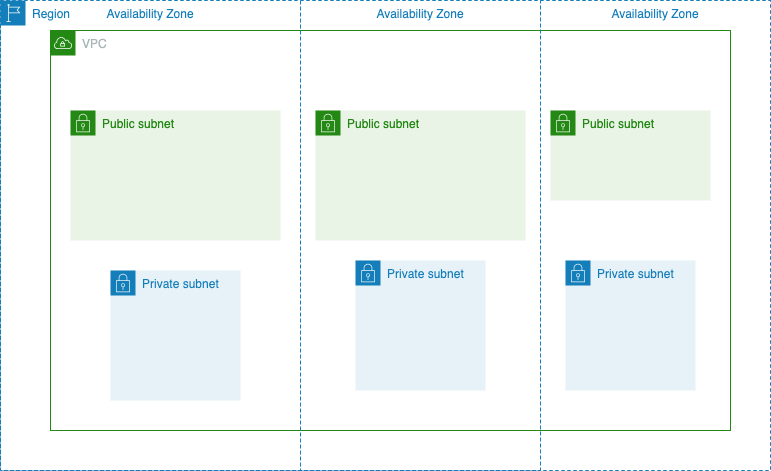

Now, how do we use this in the cloud? Cloud providers such as AWS or GCP typically would have a global network infrastructure connecting multiple data centers around the world. Usually they are divided into regions (for example, asia-southeast2 is the Jakarta region in GCP and ap-northeast-1 is the Tokyo region in AWS). This would allow customer to adjust their deployment location according to their needs (in terms of latency, regulatory compliance, cost, etc). Many services in the cloud would also be designed to be regional. That is, the specific resource that you create using a service within a cloud provider would be physically located in that region and can’t span multiple region. This could be important. For example, there might be a regulation where the data of your customer can’t leave your country (this is usually found in a highly regulated sector like healthcare or finance). Also while the speed of light is very fast, it’s still finite. Therefore, connecting your user through a needlessly long distance might not be a good idea since it adds unnecessary latency. It’s not unusual that cloud provider (especially larger one) would have multiple data centers inside a region. Therefore, you might see a subdivision of region inside that cloud provider global network as an abstraction of actual data centers. For example, GCP has zones and AWS has availability zones (AZ). Those can reflects one or more actual data centers, which you (usually) does not need to worry.

In an on-promise network, you manage (or use) a data center for your own company. This allows you to logically isolate the compute resources used by your company. You might also have the resources divided over several virtual LANs (VLANs) as another logical abstraction to match specific business purpose. How would you do the same thing on the cloud? This is where a virtual private cloud (VPC) comes in.

Virtual Private Cloud (VPC)

Simply said, a virtual private cloud is a logically isolated network used to represent the structure of an on-premise network in the cloud. This logical abstraction is useful for you to group together infrastructure and maintains security (through firewall on the VPC and other means of controlling access to the VPC). On AWS and GCP, this is a global resource, meaning that it spans all regions and (availability) zones.

When you imagine VPC as a LAN, the equivalent for VLANs would be subnets. A subnet, technically, is a range of IP address within your VPC that is used to group together resources. In GCP, subnet is a regional resources, while in AWS subnet is an AZ resource (which means that you can’t create a multi-AZs spanning subnet — and this is why you always read the documentation 😃). In a VPC, you are assigned an IP range for resources inside that VPC.

IP Address

Internet Protocol (IP), simply said, is a set of rules that standardized and governs how data is transmitted in the internet. An IP address is a unique numerical identifier assigned to a host or routers on the internet (and which actually corresponds to a network interface instead of the actual host — this is why you could set up a VM on the cloud that has multiple IP address, just attach multiple network interface!) that can be used as a source or destination address for the communication.

In this article we are going to focus on IPv4 protocol, since the author never actually use IPv6. Using IPv4, an IP address is a 32-bits (4 bytes) address, written in dotted decimal notation. So, each byte would be represented as a number from 0 to 255 and separated by dots. For example, an IPv4 address could be 172.10.136.84. Since IP address is hierarchical, a network would corresponds to a contiguous block of IP addresses. Therefore, when working with VPC and subnets, you would be working with a range of IP addresses. For example, you might want your VPC to have the (private) IP addresses of 172.31.0.0 to 172.31.255.255 (so $256 \times 256 = 65536$ IP addresses). A private IP address is IPv4 address not reachable over the internet. This is typically used for communication of internal resources.

A compact way to represent this IP range would be to use CIDR (Classless Inter-Domain Routing) notation. We write this IP range as (prefix)/(32 - prefix length) (here, 32 is the length of IPv4 address, in bits), where prefix is the block of IP address and the prefix length is in power of two. So for our example above, we would write the prefix as 172.31.0.0 and the prefix length as 16 (since $65536 = 2^{16}$), so our range in CIDR notation would be 172.31.0.0/16. Depending on your cloud provider, the VPC size might be limited. For example, on AWS the VPC IP range is (by default, can be adjusted on request) limited to 5 CIDRs range from /16 to /28. Always consults the documentation of your cloud provider for stuff like this.

Another way of calculating CIDR block is by using a subnet mask. That is, we specify a 32 bits four-dotted decimal number as a bitmask which encodes the prefix length. For example, suppose that we have an IP address of 172.31.255.10 and a subnet mask of 255.255.0.0. We first convert the subnet mask to its binary representation: 11111111 11111111 00000000 00000000. We also convert the IP address into its binary representation: 10101100 00011111 11111111 00001010. Doing bitwise AND operation between the subnet mask and the IP address results in

11111111 11111111 00000000 00000000

10101100 00011111 11111111 00001010

———————————————— (AND)

10101100 00011111 00000000 0000000

Which yields (after converting back to decimals) 172.31.0.0 as our IP prefix.

In general the number of available hosts on our IP range is $2^{(32-\text{prefix length})} - 2$, where the 2 subtracted IP address is the one reserved for network and broadcast address. In our example above, the network address would be 172.31.0.0 and the broadcast address 172.31.255.255. The actual number might varies between implementation by the cloud provider (as they might reserve additional IP address for another purpose), so again, check the documentation.

Subnet

Back to our VPC. If previously I used VLANs as an illustration for subnet, let’s now be a bit more precise. In general, “subnetting” is (the act of) splitting the block of address into several parts internally, while externally it’s still treated as a part of the same network. A subnet is a result of subnetting. For example, in our VPC with IP range 172.31.0.0/16 in CIDR notation can be split into subnet A with range 172.31.1.0/24 (with range 172.31.1.0 to 172.31.1.255) and a subnet B with range 172.31.2.0/27 (with range 172.31.2.0 to 172.31.2.31). As we can see, the size of the subnet need not be the same, but it can’t intersect. This is where subnet mask come in handy. Given an IP address and a subnet mask, we can determine which subnet does this IP address belong by doing the calculation we just did above.

As a last part, here is an illustration of a VPC on an AWS region (with zero compute resource) which have several subnets on multiple availability zones.